When Can You Wear White Pants Again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/c2/93c23aac-9936-44eb-b1e4-90bf0852b8e7/blue-pink-baby-clothes.jpg)

Little Franklin Delano Roosevelt sits primly on a stool, his white skirt spread smoothly over his lap, his easily clasping a hat trimmed with a marabou feather. Shoulder-length hair and patent leather party shoes complete the ensemble.

We find the look unsettling today, even so social convention of 1884, when FDR was photographed at age 2 1/2, dictated that boys wore dresses until age half dozen or seven, too the time of their first haircut. Franklin's outfit was considered gender-neutral.

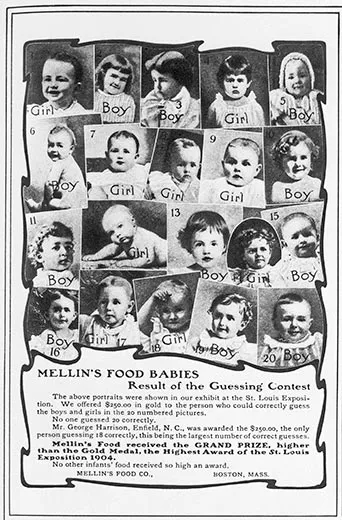

Only nowadays people just accept to know the sex of a baby or immature child at offset glance, says Jo B. Paoletti, a historian at the University of Maryland and author of Pinkish and Blue: Telling the Girls From the Boys in America, to be published after this year. Thus we meet, for example, a pink headband encircling the baldheaded head of an infant girl.

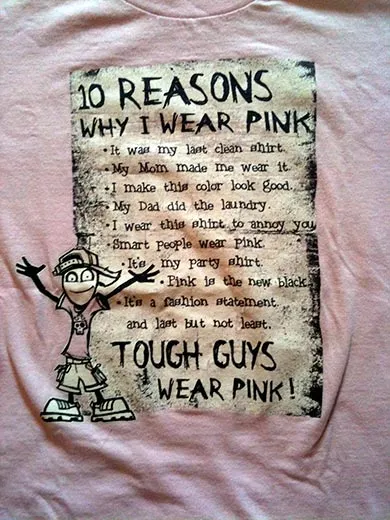

Why have young children's clothing styles changed then dramatically? How did we finish up with two "teams"—boys in blue and girls in pinkish?

"Information technology's really a story of what happened to neutral clothing," says Paoletti, who has explored the meaning of children's wearable for xxx years. For centuries, she says, children wore squeamish white dresses upwards to age 6. "What was once a affair of practicality—you wearing apparel your baby in white dresses and diapers; white cotton fiber can be bleached—became a affair of 'Oh my God, if I dress my baby in the wrong thing, they'll grow up perverted,' " Paoletti says.

The march toward gender-specific clothes was neither linear nor rapid. Pinkish and bluish arrived, along with other pastels, equally colors for babies in the mid-19th century, yet the two colors were not promoted as gender signifiers until simply before World State of war I—and fifty-fifty then, information technology took time for popular civilisation to sort things out.

For case, a June 1918 commodity from the trade publication Earnshaw'south Infants' Section said, "The generally accustomed rule is pinkish for the boys, and blueish for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the male child, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl." Other sources said blue was flattering for blonds, pink for brunettes; or bluish was for blue-eyed babies, pink for dark-brown-eyed babies, according to Paoletti.

In 1927, Time magazine printed a chart showing sexual activity-appropriate colors for girls and boys according to leading U.S. stores. In Boston, Filene's told parents to dress boys in pink. And so did All-time & Co. in New York City, Halle's in Cleveland and Marshall Field in Chicago.

Today's colour dictate wasn't established until the 1940s, as a result of Americans' preferences as interpreted by manufacturers and retailers. "It could have gone the other way," Paoletti says.

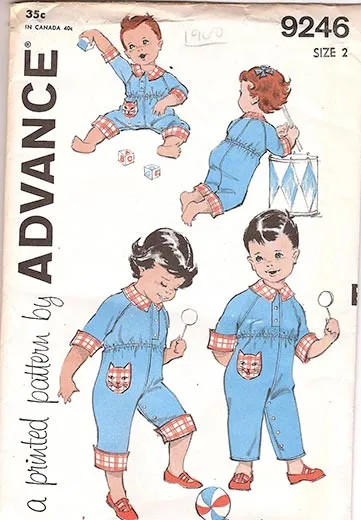

So the baby boomers were raised in gender-specific vesture. Boys dressed like their fathers, girls like their mothers. Girls had to wear dresses to school, though unadorned styles and tomboy play clothes were acceptable.

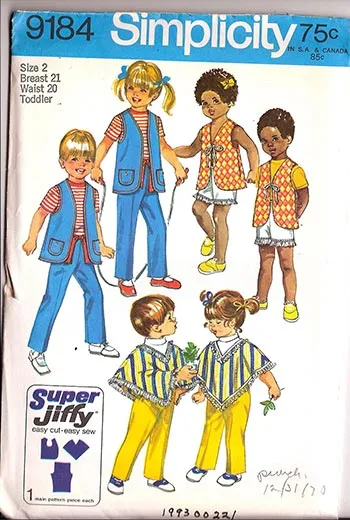

When the women's liberation movement arrived in the mid-1960s, with its anti-feminine, anti-way message, the unisex wait became the rage—just completely reversed from the fourth dimension of young Franklin Roosevelt. Now young girls were dressing in masculine—or at least unfeminine—styles, devoid of gender hints. Paoletti found that in the 1970s, the Sears, Roebuck catalog pictured no pink toddler vesture for two years.

"I of the ways [feminists] thought that girls were kind of lured into subservient roles as women is through clothing," says Paoletti. " 'If we dress our girls more similar boys and less like frilly petty girls . . . they are going to have more options and feel freer to be agile.' "

John Money, a sexual identity researcher at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, argued that gender was primarily learned through social and environmental cues. "This was one of the drivers back in the '70s of the argument that it's 'nurture not nature,' " Paoletti says.

Gender-neutral wear remained popular until about 1985. Paoletti remembers that twelvemonth distinctly because information technology was between the births of her children, a girl in '82 and a boy in '86. "Suddenly information technology wasn't just a blue overall; it was a blue overall with a teddy comport holding a football," she says. Disposable diapers were manufactured in pink and bluish.

Prenatal testing was a big reason for the modify. Expectant parents learned the sexual activity of their unborn baby then went shopping for "girl" or "male child" merchandise. ("The more you individualize article of clothing, the more you can sell," Paoletti says.) The pinkish fad spread from sleepers and crib sheets to big-ticket items such every bit strollers, car seats and riding toys. Affluent parents could conceivably decorate for baby No. 1, a girl, and start all over when the next child was a male child.

Some young mothers who grew upward in the 1980s deprived of pinks, lace, long pilus and Barbies, Paoletti suggests, rejected the unisex look for their own daughters. "Even if they are still feminists, they are perceiving those things in a dissimilar light than the baby boomer feminists did," she says. "They think even if they desire their girl to be a surgeon, there's nix wrong if she is a very feminine surgeon."

Another important factor has been the rise of consumerism among children in recent decades. Co-ordinate to child development experts, children are just becoming conscious of their gender between ages iii and 4, and they practise not realize it's permanent until age half dozen or vii. At the same time, however, they are the subjects of sophisticated and pervasive advertising that tends to reinforce social conventions. "So they call up, for example, that what makes someone female is having long pilus and a apparel,'' says Paoletti. "They are so interested—and they are and then adamant in their likes and dislikes."

In researching and writing her book, Paoletti says, she kept thinking about the parents of children who don't conform to gender roles: Should they wearing apparel their children to conform, or allow them to express themselves in their dress? "I matter I can say now is that I'chiliad not real keen on the gender binary—the thought that you have very masculine and very feminine things. The loss of neutral clothing is something that people should think more about. And in that location is a growing demand for neutral clothing for babies and toddlers at present, too."

"At that place is a whole community out there of parents and kids who are struggling with 'My son really doesn't want to article of clothing boy dress, prefers to article of clothing girl clothes.' " She hopes ane audience for her book will exist people who written report gender clinically. The fashion world may take divided children into pinkish and blue, but in the world of real individuals, not all is black and white.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misattributed the 1918 quotation most pinkish and bluish clothes to the Ladies' Home Journal. It appeared in the June 1918 effect of Earnshaw'due south Infants' Department, a trade publication.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/when-did-girls-start-wearing-pink-1370097/

Postar um comentário for "When Can You Wear White Pants Again"